Wendy Millar (loyalist) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Wendy Millar (born 1944) also known as "Bucket" and "Queen of the UDA" is a Northern Irish

Shortly afterwards, Millar established the first UDA women's unit on the Shankill Road. Although there were other women's units set up in other areas, the Shankill Road group was particularly active and highly visible on account of the beehive hairstyles the women typically wore.Taylor, Peter (1999). ''Loyalists''. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. p.136 In May 1974 during the

Shortly afterwards, Millar established the first UDA women's unit on the Shankill Road. Although there were other women's units set up in other areas, the Shankill Road group was particularly active and highly visible on account of the beehive hairstyles the women typically wore.Taylor, Peter (1999). ''Loyalists''. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. p.136 In May 1974 during the

Millar, her sons and son-in-law were part of the

Millar, her sons and son-in-law were part of the

Retrieved 18 May 2012 Shortly after his return he was abducted and killed by the

loyalist

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cro ...

and a founding member of the Ulster Defence Association

The Ulster Defence Association (UDA) is an Ulster loyalism, Ulster loyalist paramilitary group in Northern Ireland. It was formed in September 1971 as an umbrella group for various loyalist groups and Timeline of Ulster Defence Association act ...

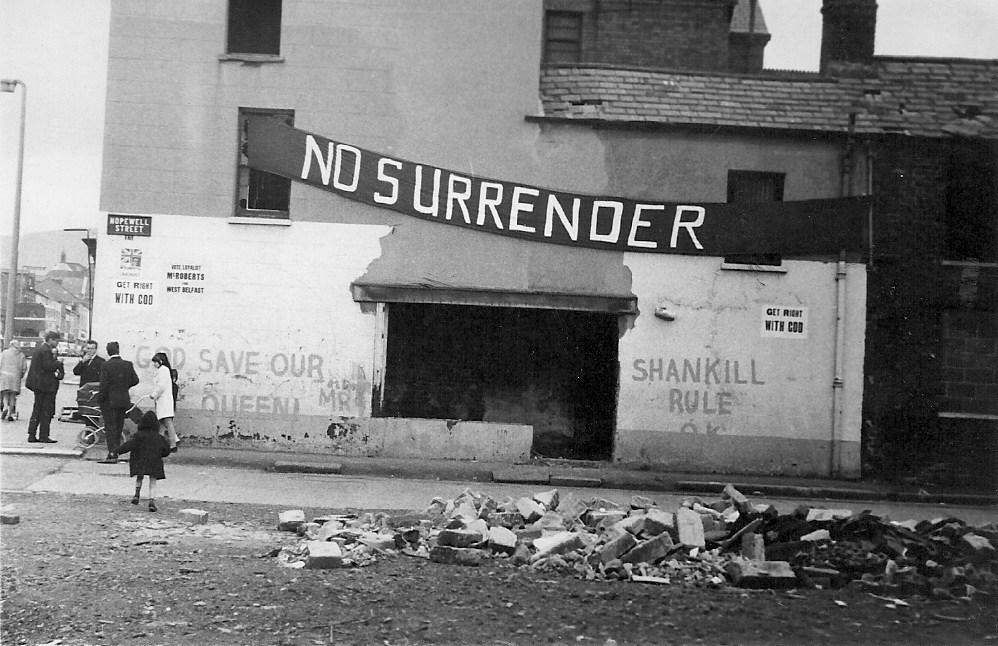

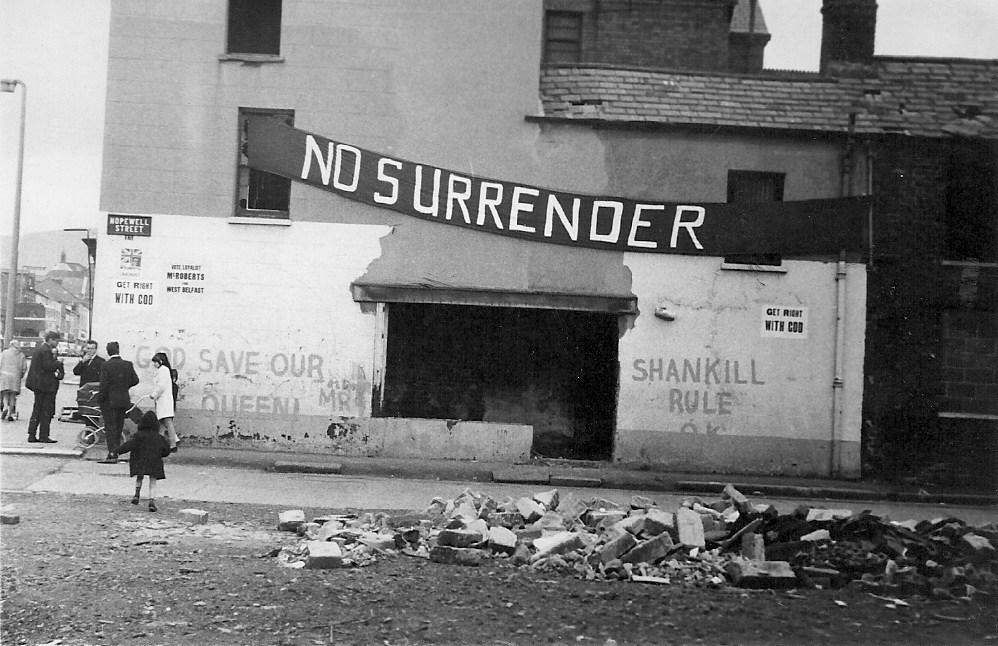

(UDA). She established the first UDA women's unit on her native Shankill Road

The Shankill Road () is one of the main roads leading through West Belfast, in Northern Ireland. It runs through the working-class, predominantly loyalist, area known as the Shankill.

The road stretches westwards for about from central Belfast a ...

in Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdo ...

. Her two sons Herbie and James "Sham" Millar are also high-profile UDA members and her daughter's husband is former West Belfast brigadier "Fat" Jackie Thompson.

UDA women's unit

Born into aProtestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

family in Belfast, Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

in about 1944, Millar was raised on the staunchly loyalist Shankill Road. She was one of the founding members of the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) which was set up in September 1971 as an umbrella organisation for the many local vigilante groups that had sprung up in loyalist areas to protect their communities from attacks by Irish republicans

Irish republicanism ( ga, poblachtánachas Éireannach) is the political movement for the unity and independence of Ireland under a republic. Irish republicans view British rule in any part of Ireland as inherently illegitimate.

The developm ...

following the outbreak of the violent religious-political conflict known as the Troubles

The Troubles ( ga, Na Trioblóidí) were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it is sometimes described as an "i ...

in the late 1960s. She had the nicknames of "Bucket" on account of her outspoken, loud-mouthed personality, and "Queen of the UDA" for her devotion to the paramilitary organisation. Described as tough and fearless, she was a heavy smoker and a "leading light in UDA circles".

Shortly afterwards, Millar established the first UDA women's unit on the Shankill Road. Although there were other women's units set up in other areas, the Shankill Road group was particularly active and highly visible on account of the beehive hairstyles the women typically wore.Taylor, Peter (1999). ''Loyalists''. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. p.136 In May 1974 during the

Shortly afterwards, Millar established the first UDA women's unit on the Shankill Road. Although there were other women's units set up in other areas, the Shankill Road group was particularly active and highly visible on account of the beehive hairstyles the women typically wore.Taylor, Peter (1999). ''Loyalists''. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. p.136 In May 1974 during the Ulster Workers' Council strike

The Ulster Workers' Council (UWC) strike was a general strike that took place in Northern Ireland between 15 May and 28 May 1974, during "the Troubles". The strike was called by unionists who were against the Sunningdale Agreement, which had b ...

, the general secretary

Secretary is a title often used in organizations to indicate a person having a certain amount of authority, power, or importance in the organization. Secretaries announce important events and communicate to the organization. The term is derived ...

of the Trades Union Congress

The Trades Union Congress (TUC) is a national trade union centre

A national trade union center (or national center or central) is a federation or confederation of trade unions in a country. Nearly every country in the world has a national tra ...

, Len Murray

Lionel Murray, Baron Murray of Epping Forest, (2 August 1922 – 20 May 2004) was a British Labour Party politician and trade union leader.

Early life

Murray was born in Hadley, Shropshire, the son of a young unmarried woman, Lorna Hodskinson ...

went to Belfast to lead the striking shipyard workers on a 'back to work' march. Just as the marchers set out for the Harland and Wolff

Harland & Wolff is a British shipbuilding company based in Belfast, Northern Ireland. It specialises in ship repair, shipbuilding and offshore construction. Harland & Wolff is famous for having built the majority of the ocean liners for the W ...

shipyard, furious members of the Shankill Road women's unit arrived on the scene and proceeded to pelt Murray with flour, eggs and other objects. Glen Barr

Albert Glenn Barr OBE (19 March 1942 – 24 October 2017) was a politician from Derry, Northern Ireland, who was an advocate of Ulster nationalism. For a time during the 1970s he straddled both Unionism and Loyalism due to simultaneously holdi ...

, the chairman of the strike co-ordinating committee witnessed the assault. In an interview with British journalist Peter Taylor Peter Taylor may refer to:

Arts

* Peter Taylor (writer) (1917–1994), American author, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction

* Peter Taylor (film editor) (1922–1997), English film editor, winner of an Academy Award for Film Editing

Politic ...

he described the UDA women with their beehives as looking "quite frightening" and resembled six feet tall Amazons

In Greek mythology, the Amazons (Ancient Greek: Ἀμαζόνες ''Amazónes'', singular Ἀμαζών ''Amazōn'', via Latin ''Amāzon, -ŏnis'') are portrayed in a number of ancient epic poems and legends, such as the Labours of Hercules, ...

. Barr had had encounters with the women on previous occasions and was intimidated by them.

Another group, the Sandy Row women's unit gained notoriety in July 1974 when its commander Elizabeth "Lily" Douglas ordered her "Heavy Squad" (a gang within the unit who meted out punishment beatings) to bring Protestant single mother Ann Ogilby to a "Romper Room" where she was subsequently beaten to death.Simpson, Alan (1999). ''Murder Madness: True Crimes of The Troubles''. Dublin: Gill & McMillan. pp.38–39 "Romper Rooms" were locations where UDA victims were brought to be "rompered" which was a UDA slang term for a torture and beating session prior to "execution". The name derived from the children's television programme

A television show – or simply TV show – is any content produced for viewing on a television set which can be broadcast via over-the-air, satellite, or cable, excluding breaking news, advertisements, or trailers that are typically placed betw ...

. The brutality of the attack greatly shocked the Protestant community and the UDA leadership which had not sanctioned the killing. Douglas and ten others were imprisoned for Ann Ogilby's murder and the unit was subsequently stood down.Wood, p.59 Jean Moore and later Hester Dunn

Hester Rogers (born 1940) is a Northern Irish former loyalist activist and writer who was a member of the Ulster Defence Association's (UDA) political wing during the period of religious-political conflict known as the Troubles. She headed the UDA' ...

headed the UDA women's department from the UDA headquarters on Gawn Street, in east Belfast.Dillon, Martin; Lehane, Denis (1973). ''Political murder in Northern Ireland''. Penguin. p.232Wood, Ian S. (2006). ''Crimes of Loyalty: a History of the UDA''. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p.94 The women's units were typically involved in local community work and responsible for the assembly and delivery of food parcels to UDA prisoners. The latter activity was a source of pride for the UDA.Women Loyalist Paramilitaries in Northern Ireland: Duty, Agency and Empowerment – A Report from the Field". ''All Academic Research''. Sandra McEvoy. 2008. p.16

As the Northern Ireland conflict continued over the years and decades, Millar remained within the UDA to serve as a loyal and dedicated member. Her sons Herbie (born c.1965) and James "Sham" Millar (born c.1966) later became high-profile figures inside the organisation, and her daughter married high-ranking member "Fat" Jackie Thompson.

Johnny Adair and C Company

Millar, her sons and son-in-law were part of the

Millar, her sons and son-in-law were part of the UDA West Belfast Brigade

The UDA West Belfast Brigade is the section of the Ulster loyalist paramilitary group, the Ulster Defence Association (UDA), based in the western quarter of Belfast, in the Greater Shankill area. Initially a battalion, the West Belfast Brigade emer ...

's C Company 2nd Battalion based on the Shankill Road which in the early 1990s came under the command of Johnny Adair

John Adair (born 27 October 1963), better known as Johnny Adair or Mad Dog Adair, is an Ulster loyalist and the former leader of the "C Company", 2nd Battalion Shankill Road, West Belfast Brigade of the Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF). This was a ...

who was made West Belfast brigadier. On 10 August 1992, the UDA was proscribed by the British government. Up until then it had been a legal organisation. Millar became an ardent supporter of Adair and set herself up as resident cook in the "Big Brother House", a community centre in the lower Shankill which Adair used as his headquarters and where his henchmen brought disobedient locals for punishment beatings. In the early 2000s, however, Millar found herself deeply embroiled in an internal feud within the UDA.

On 24 December 2002 as part of the feud, a rival, anti-Adair unit set fire to Millar's caravan home in Groomsport

Groomsport () is a village and townland two miles north east of Bangor in County Down, Northern Ireland. It is on the south shore of Belfast Lough and on the north coast of the Ards Peninsula. Groomsport has a population of 3,005 people accordin ...

park, burning it to the ground. Millar, who was in Belfast at the time, was devastated by the arson attack as she regarded the caravan as a second home for her and her 63-year-old husband. Describing herself as a "community worker in the lower Shankill" who worked with "the young and old, trying to make life better for them", she claimed she knew the identity of the perpetrators calling them "the scum of the earth". Ulster Democratic Party

The Ulster Democratic Party (UDP) was a small loyalist political party in Northern Ireland. It was established in June 1981 as the Ulster Loyalist Democratic Party by the Ulster Defence Association (UDA), to replace the New Ulster Political Res ...

member and staunch Adair ally John White laid the blame firmly on the North Belfast UDA. She had previously suffered a stroke and told the News Letter'' how saddened she was to have lost the caravan, "I have a lot of memories of the place and the people there. I used to go down to the caravan in March and stay there until around the end of September because I loved it so much". Following the incident, Millar turned her Shankill Road home into a fortress in case of further attacks.

In early 2003, Adair, who was imprisoned at the time, allegedly gave orders from his prison cell for the elimination of his biggest rival John Gregg, leader of the UDA South East Antrim Brigade

The UDA South East Antrim Brigade was previously one of the six brigades of the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) and are heavily involved in the drug trade. It is claimed they control "100%" of an illegal drugs network in south-east Antrim, No ...

. C Company's young military commander Alan McCullough hastened to do Adair's bidding and orchestrated Gregg's killing. The brigadier was shot dead in a taxi near Belfast docks along with Rab Carson after the men had returned from a Rangers F.C.

Rangers Football Club is a Scottish professional football club based in the Govan district of Glasgow which plays in the Scottish Premiership. Although not its official name, it is often referred to as Glasgow Rangers outside Scotland. The fou ...

match in Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

on 1 February 2003. The killing of Gregg infuriated the UDA Inner Council which had already expelled Adair and his entire C Company unit from the mainstream organisation the previous September.The Inner Council was the UDA leadership made of the brigadiers who represented the six brigade areas. Gregg enjoyed much popularity among the loyalist community for his attempted assassination of Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( , ; en, " eOurselves") is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active throughout both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Gri ...

president Gerry Adams

Gerard Adams ( ga, Gearóid Mac Ádhaimh; born 6 October 1948) is an Irish republican politician who was the president of Sinn Féin between 13 November 1983 and 10 February 2018, and served as a Teachta Dála (TD) for Louth from 2011 to 2020 ...

in 1984. On the day of Gregg's funeral, carloads of angry UDA men led by South Belfast brigadier Jackie McDonald

John "Jackie" McDonald (born 2 August 1947) is a Northern Irish loyalist and the incumbent Ulster Defence Association (UDA) brigadier for South Belfast, having been promoted to the rank by former UDA commander Andy Tyrie in 1988, following J ...

convened on Adair's Boundary Way stronghold in the lower Shankill. McDonald also detested Adair and had been one of the UDA leaders who sanctioned his expulsion. Adair's wife, Gina, John White, and about 20 of his supporters including Millar's sons were compelled to leave Northern Ireland. The rogue group headed for Scotland and afterwards England.McDonald, Henry & Cusack, Jim (2004). ''UDA: Inside the Heart of Loyalist Terror''. Penguin Ireland. p.386

Expulsion from Northern Ireland

Millar believed her years of devotion to the organisation would allow her to remain in her Shankill Road home. Her pleas fell on deaf ears as the UDA Inner Council maintained she was fully aware of her sons' drug-dealing and loan-sharking activities, and that they had stolen over ten thousand pounds of UDA funds. Two weeks after the Adair faction was kicked out of Northern Ireland, Millar was also ordered to leave and told she'd be executed if she failed to comply. She reluctantly joined her sons and the other Adair supporters inBolton

Bolton (, locally ) is a large town in Greater Manchester in North West England, formerly a part of Lancashire. A former mill town, Bolton has been a production centre for textiles since Flemish people, Flemish weavers settled in the area i ...

where they became known as the "Bolton Wanderers". Adair's former friend Mo Courtney

William Samuel "Mo" Courtney (born 8 July 1963) is a former Ulster Defence Association (UDA) activist. He was a leading figure in Johnny Adair's C Company, one of the most active sections of the UDA, before later falling out with Adair and servi ...

had already defected back to the mainstream UDA and was appointed commander of Adair's West Belfast Brigade in lieu of Millar's son-in-law, "Fat" Jackie Thompson who had served as brigadier during Adair's imprisonment. He had also fled to England.

Millar could not adjust to her new life as an exile in England and felt homesick for Northern Ireland. Defying the UDA leadership, she returned home and immediately applied to the Housing Executive for a house in Bangor, County Down

Bangor ( ; ) is a city and seaside resort in County Down, Northern Ireland, on the southern side of Belfast Lough. It is within the Belfast metropolitan area and is 13 miles (22 km) east of Belfast city centre, to which it is linked ...

. Once the UDA in Belfast discovered she had disobeyed orders by returning, she was immediately subjected to threats and had the windows of her home smashed with bricks. When English journalists called to her house she loudly announced, "I'm staying, no-one will put me out!". The next day the Bolton hideout her sons were sharing with Gina Adair, "Fat" Jackie Thompson, and Sham's girlfriend was raked with machinegun fire. Nobody was injured in the attack which was carried out by Alan McCullough as a means to ingratiate himself with Mo Courtney and the new C Company leadership to be allowed to return home.cowan "Family fears for fate of missing loyalist". ''The Guardian''. Rosie Cowan. 2 June 2003Retrieved 18 May 2012 Shortly after his return he was abducted and killed by the

Ulster Freedom Fighters

The Ulster Defence Association (UDA) is an Ulster loyalist paramilitary group in Northern Ireland. It was formed in September 1971 as an umbrella group for various loyalist groups and undertook an armed campaign of almost 24 years as one of t ...

(UFF), a covername for the UDA.McDonald & Cusack, ''UDA'', p.393

Notes

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Millar, Wendy Ulster Defence Association members UDA C Company members 1944 births Paramilitaries from Belfast Living people